CYRANO'S JOURNAL®

THEATER / Kulturkampf | 24-Oct-07, 08:30 AMA dialogue on theater and contemporary artsBy John Steppling and Guy Zimmerman | Summer 2005(Part Two) |

http://www.cjonline.org

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED, 2005 CJONLINE.ORG & SPECIFIC AUTHORS. PLEASE SEE OUR COPYRIGHT NOTICE.

"Any playwright seeking to address social injustice of one kind or another by way of melodrama is by definition doing his or her cause more harm than good..."

-G. Zimmerman

It wants to pretend it has no secrets. So modern rituals are often empty and feel hollow. Theatre often feels hollow and pointless. I think Nixon is so fascinating because his madness was so wrapped in the cloak of this obsessive idea of secrecy. And that he was so grand and almost Shakespearean. Bush and Cheney are dwarf-like and petty --- and in a sense even more destructive for it. Though of course it's not really them, they are just the goofy poster children for a larger system of madness.

There is the hidden desire of the playwright, and then there is the hidden desire of the play itself. I think it's obvious, when one looks at studio films or cheap mystery writing that the plot stops being interesting when things get explained. All talk about sub-text is based on an assumption about an explainable world. Now when you speak of the turning of the wheel.....I think of Reich again. Of people's lack of health. Not just mental health, but total health. The fundamental primal sickness of being human. That is part of what tragedy addressed and it's amazingly absent today. Is this part of the Enlightenment inheritance? Partly I am guessing it is --- but it also how Capitalism has eclipsed thought through a distortion of science and through advertising. The consumption stage of capitalism is here.....people think they are what they buy. People perform the role of themselves --- dutiful consumer. Today's writing programs want students to have it all explained ahead of time. They encourage notions like 'closely observed detail'. God I hate that kind of shit. A good eye is of almost no use for a writer or painter or anyone else. Look all that ISN'T in a Beckett play. Look at what is missing in Pinter. The negative space, like that in much Asian pictorial work, is what matters in the end.

Listening to your thoughts on Girard I am reminded of Fassbinder --- the most Girardian of artists. Watch In a Year of 13 Moons....or Merchant of Four Seasons, or Petra Von Kant. Fassbinder understood, instinctively, the trigger for sado-masochistic revenge and how demomizing works. Look at the current state of the quisling press; how a Castro is turned into a monster but not a Tony Blair. Amazing. Look at how Chavez is demonized now in Venezuela. This society needs its enemies. I feel I need to refine a bit this notion of mystery and the unknown. It's all too easy for people to take this in some sorry-assed new age crystal gazing way --- too easy to think, as I've said before, that the material conditions don't matter. It is only from the concrete and the specific that one can explore those hidden dimensions. What you say about Girard and Kafka is really impressive and about exactly correct, I think. Also, I find myself returning often to a lot of pre-modern texts. There is a trap here, however. A sort of weird anarchistic longing and I am aware of it. It can quickly morph into something quite reactionary. One need only look at Heidegger.....perhaps the greatest philosopher of the century, and essentially a fascist. What does one do with that knot? Still, reading Dante or early Hindu philosophy is an urgent need. Buddhist scripture and the early Christian mystics --- all essential.

“One does not know speech by means of words, but through silence”. Rene Daumal.

I believe Freud said that dumbness in dreams was often a sign of death. The absence of speech, of talking, is a very powerful thing in theatre. On stage, the dream state, the silence is always more intense than the dialogue. The very spaces between the words have great meaning and great actors are always the ones who listen the best and can feel those spaces. Lee Kissman was my favorite actor in that respect.

So, now we have a theatre of talk and of chatter. Of behaviour and not of questioning. It corresponds I think with the fatal last gasps of Empire --- of a waste economy and an escalating need for violence (Girard again). The simply irrational spectacle before us. Theatre and those who run it, and those who "review" it seem lost and clueless. A people who can't leave their cell phones turned off is a people in deep pain....in deep delusion. On that thought, once more back to you.

JS

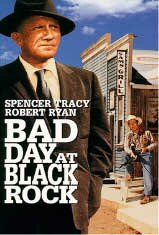

Guy; The comments on suffering are so exactly right, and so pertinent. I watched an old John Sturgis film, Bad Day at Black Rock, with Spencer Tracy. Now it's a quite neglected film, but I mention it here because of Tracy --- an actor who suffered totally, all the time. Brando suffered, of course, and others....and I've seen Gielgud on stage, and he suffered tremendously....where it always seemed to me that Olivier didn't. Kenneth Branagh doesn't, and this is his great limitation. Two of today's best actors are Jeff Wright and Ray Winstone...both suffer. This suffering has a cost --- and this becomes a complex question. If the actor is not willing to suffer in public (as you put it)....if he can't somehow, then he will always be doing something technical --- something that I feel ends up being about not listening. If you really listen, then you suffer.

A note though on this idea. Adorno saw all expression as an expression of suffering. Joy was impossible, he thought, because perhaps it did not yet exist. Bliss, well, forgetaboutit. So the suffering we speak of is also inherent in the getting on stage....not just a subjective suffering of the individual artist or actor. It is there in the humiliation of asking to be looked at.

Paul Ricoeur has talked about myth, ritual, and the sacred ---regards language--- all of which relates closely to what we [were] talking about in terms of theatre. To look at something, even the universe, as sacred, is to make it sacred. To (as Ricoeur puts it) consecrate it. Here too Bachelard is relevant --- the interior and the exterior --- the exterior tends to be the profane, so how does this relate to stage space? To doors or windows on stage? The function of myth (says Ricoeur) is to fix the paradigms of the ritual and to sacralize them. Now, this is where language enters the picture I suspect. What is our memory of extraordinary events? Why do people return to specific places? These days it's usually just hyped sentimental bullshit.....placing flowers at Princess Di's death spot....or even the stage managed 9-11 stuff......its all ersatz grief. It's part of the strategy of control. Still, birth and death are hard to secularize ---and here one feels the scientific is close to the military. The merchants of death march onward, trying to control the mythic, trying to neutralize the real power of tragedy. I am talking all over the place here, but I come back to reading early texts -- the Bible for example, or the Bhagvad Gita, or a Parmenides. How does the language work in such texts? I think Kafka was a Biblical writer, and I think this is what Benjamin understood. He wrote sacred texts. Melville too. The idea of parables is interesting; writers like DeGhelderode or Broch --- how everything becomes a parable. These parables suggest the prophetic --- (Ernst Bloch!!). The future -- time -- and Bly said this about Neruda I think, how he, for moments, became someone who lived in a future. Theatre has been made into a silly and trivial pastime, something for amusement and distraction. Brecht tried his whole life to engage with the sacred and with the political. Whatever he said about it, that's what he was doing. Pinter and Genet were (and are) using the theatre to point toward the mysterious and unknown.

So, I return once again, to product. When a society (and its artists) embrace the idea of product, then the engagement we're talking about, or trying to, is stalled. The product is there to be consumed, not experienced. Consumption is fine for popcorn or CD players I guess, but not for art. The language of sacred texts, and let me use the Old Testament, is written to call forth questions of immensity. I find this in great art as well. I leave a Pinter play in a state of hyper sensitivity, of awe and humility.....and maybe of fear. It's important to note that this process of engagement is always historical -- meaning for me political to a degree. You cannot write something today that ignores, say, Iraq and US military bases around the globe. You cannot ignore cluster bombing wedding parties and killing children, and you cannot ignore Guantanamo Bay. This doesn't mean you write agitprop --- for that is to ignore the sacred. The sacred, is however, or should be, connected to material history. The artist must understand this dialectic I think. Guantanamo Bay is in the play even if it's not mentioned. Or rather, it should be. Shakespeare knew he couldn't say certain things out loud --- so he found other ways to express them. All great artists do this. The iconic picture from Abu Ghraib, of the man in a hood with electrodes and wires standing on a box --- this image is impossible to ignore whenever you start to create something --- and to pretend it's not there is to fail, immediatly, as an artist. But back to the Old Testament. The Book of Job, a great example. There is no world outside of God and Job (did Beckett follow this as closely as it seems he did?). What is this story about? We could talk about it for several years, probably. My point here is that the central question in Job is, in a way, the central question for all writing. I may not even be able to describe exactly what the question is, that is why it's so significant. I can, however, feel the pull of the history and of tragedy and of the mythic (or unknown). It is about the creating of a "world". Now what do I mean by creating a world? I honestly am not sure --- I say it to students a lot....because I feel the absence of a world in their work. I feel the absence of history. I feel this creating a world means to stand in front of one's own irrelevance and accept it -- and then to look at the mountains and to listen. Here we are back at the door on stage. Here we are staring at the night sky. This is dharma....this is the journey. No world, no tragedy, then no journey.

If I watch a great film, I get something close to what I get in theatre. I don't have the immediacy, but I still have something. Today one sees very little that is worth while. Spielberg is a fascist. Simply put. This latest piece of dog shit --- War of the Worlds....featuring everyone's favorite Scientologist....is the perfect piece of fascist devotion. Leni Reifenstal would be proud (not to mention things like the new Bochco series "Over There"). What do audiences 'feel' when they leave the cineplex after WoW? I suspect there is a diseased craving for, oh, a new pair of trainers or a chocolate ice cream --- or they lurch to their SUVs and drive really fast to escape the nausea. I don't know. I do know they tell themsleves they are happy and lucky to be alive in America. Now, institutional theatre and the funding organizations of same, are a lot like NGOs. They provide a kind of band aid to quell real revolt. Arundhati Roy -- who I adore -- is really smart on this topic. The NGOs, the darlings of the liberal elite, are there to keep things stable....to help those victims of Imperial aggression....but not to change the system, because the system bankrolls them. So the arts organizations are like cultural NGOs. They don't much care who gets a grant, really, because to get a grant identifies you as an artist in need. An artist in need is not a success ---- not a Spielberg. They are careful though, they don't give grants to people who are "too" offensive. They really like things the way they are. Period. They don't want an artistic revolution. So, this desire for something more, it must somehow find a venue, must somehow exist in the shadows of empty doorways, so to speak. Artists must learn to live in those doorways and forget the Brie and Chablis lunches with the Taper hierarchy, or with the Public Theatre or the Long Wharf. It's a hard choice however. Artists tend to get caught up in this groveling for chump change, when they should just be telling these people to fuck off --- and go work at a factory...and I am not suggesting factory work as anything other than utter alienated toil.

Ok, well, let me touch again briefly on acting. I think your remarks are so insightful and right. I want to explore, though, this question of "playing" a character. First, the question of character needs a bit of elaboration. Then, second, the notion of unconditioned behaviour. I agree with you....I think....but I can't quite grasp what we're saying. Anyway, first the character. This continues to be a big topic for me. What is being created when one writes a "character"? Either on stage, in a film, or in a novel....or an epic poem. What is being done? Here is where mimesis becomes a topic of relevance. I wonder, for instance, at biopics.....at say a movie about Jim Morrison, or anyone we know and of whom we have a lot of archival footage. Muhammed Ali, or Ray Charles. Now these are bad films...all of them....but why do they sort of have appeal? See, I think a real question is lurking around the edges of this, and it touches on what I am trying, rather hopelessly, to get at when talking about character. I think the mimetic is seductive on some level --- and yet it's also mediated by so many things. In theatre, an actor is on stage and he is playing a role, playing a character and you're right when pointing out this unconditioned quality, and maybe that accounts for why we like bio-pics....why it pulls us in. I don't know. I do think the separation you speak of is important. The audience responds to this split --- it provides an expression of the suffering of the other. The suffering is also connected to Artaud's notion of nakedness and delirium. We are most ourselves when we abandon the pretense of a 'self'. An actor who is courageous enough to stand there naked....in all senses.....is giving us the authentic, giving us what we know, deep down, is the reality of existence. It is not subjective suffering, but rather the suffering of mankind. Or, perhaps, it's more a suffering of the form itself. So maybe there are two topics here --- the first has to do with the mimetic (biopics, etc) and the second to do with something I am having trouble articulating. It is before the fact.....as I mentioned earlier. All acting is tragic, probably. Now, where does language come into this. I think we both are afraid to embark on this topic......because it's so big. So, in cowardly fashion, I take this moment to slow pitch this grapefruit back to you....

JS

John, I agree with you about Spielberg. It’s obvious that Spielberg and Reagan arrived in the same historical moment. I recall sitting in a movie theater in Philadelphia and being nauseated by the reaction of the audience to ET…and then also recognizing that the nausea was identical to what I felt when Ronald Reagan won the election. It’s obvious now, in the age of Karl Rove, that Americans are congenitally vulnerable to a certain brand of sentimental flattery. It’s that reptilian part of the brain that the fascist have forged a direct link to. Then again, as we have touched on, fascists always have a short term advantage in that they don’t mind being utterly destructive in pursuit of their ridiculous fantasies. Inevitably, however, destructive tactics end up creating strategic problems, witness the effects of hurricane Katrina on the GOP agenda.

What I was trying to get at with my comments about “conditioned” aspects of ourselves is simply that actors, as people, tend to be able to suspend a limited view of who they are and who they are not. This in itself is radical in that, as we’ve noted, the tendency to view ourselves as absolutely separate from experience and from each other is a cornerstone of what might be called the fascism of the self. The tendency to attribute solidity to the self is also, arguably, the source of social inequities – the rich man is stingy and uncaring because he identifies with what he owns and even more with the action of ownership. The identity is what he clings to more even than the things themselves, which only exist, finally, in order to support the identity. An actor playing a man of wealth is already subversive, as Brecht certainly knew. The ex-nihilo factor of the wealthy-man-performance on stage casts light on the ex-nihilo aspect of the wealthy-man-performance in the social world. The fact that his social identity is a performance (a social constuct) is, of course, what the wealthy man is desperate at all times to conceal. Wealth, after all, only exists as a matter of social convention as codified in man-made laws. This fabricated quality is a part of all aspects of identity, and the fascination with actors and with celebrity has to do with the tension between what might be called the absent and the unreal.

Many of your comments pertain to the issue of the text and the role of the text in the theatrical project. This is of course Murray (Mednick)'s great contribution to American theater, his insistance on the primary importance of the textual over the performative aspects of theater. All of theater's claim to non-triviality rests on the fact that it remains a literary art form. That this has become a controversial, perhaps even a radical notion, simply highlights how corrupt the practice of theater has become in the Anglo-Saxon world. Everyone clamors for the playwright to be exiled to the periphery of the theatrical project. Playwrights are to be smothered by condescending coddling or tossed overboard entirely as if they were, um, screenwriters. At root this is a political dynamic – without authentic texts, plays become entertainment without any non-trivial reason to exist. Murray's insistance on the text, to which we are all indebted, comes I think from a recognition that this is the lynchpin of the whole endeavor, despite how difficult it can be to defend. Theater without textual rigor = trivial activity. Theater with textual rigor = hightly potent mode of thought/feeling. And this begs obvious questions about text, and what it is that we are all doing when we write. Indeed, what is language? Lacan is an obvious place to turn if you want to grapple with this question. Chomsky too, obviously. Heidegger, no doubt, his odious politics notwithstanding. Also all the poets who Heidegger, to his credit, revered. Also all the current scientific research on the structure of the brain.

And yet all of what you will learn from these sources is already present, so to speak, when the lights rise on an actor standing on stage, looking out, ready to speak. And the task of a playwright is actually to extend that moment so that it endures for the length of a play. The task of the playwright is to preserve the purity of that moment so that it can be fully experienced, collectively, by the audience. The moment will pass, like any other, and that passing away gives rise, I would say, to what the Greeks called Catharsis. The form of tragedy – the kingly figure, the tragic flaw - is simply an attempt to provide some clothing for that inevitable passing away of what had form. Narrative and dramatic techniques are mobilized, character and setting come into play, etc. etc., but what is really being depicted or represented, or presented directly, is a coming-into-being and a passing-away, collectively experienced to the fullest degree possible.

Assuming this is true, it follows that different playwrights use very different techniques to achieve these ends. Beckett uses silence, impregnates his language with silence. Ionesco goes the other way, charging his plays with manic energy. In terms of silence, Pinter is Beckett's descendent. Those pauses that exist because there's either too much to be said or nothing that can be said. As has often been noted, your work continues in this same mode. No other American playwright has animated silence the way you have in your plays, and I've often heard you speak about the intangible quality that's there at the opening of a performance and that the play is forever chasing.

To loop back, the difference between melodrama and tragedy is the crucial distinction that progressive theater in the States has lost sight of. Melodrama is trivial, no matter what the subject matter. Tragedy, assuming it's well done, is profound regardless of subject matter. In the name of the civil right movement(s), progressives have embraced melodrama, and the result is an art form that, despite its stated intentions, actually serves a conservative agenda. Any playwright seeking to address social injustice of one kind or another by way of melodrama is by definition doing his or her cause more harm than good. Melodrama at its best only fuels a sense of indignation that is rooted in self, in ego. The Other is to blame, variously defined. The Other is to blame, and I, the viewer, am in no way implicated in what is wrong in the world. Tragedy, on the other hand, draws the viewer directly into the heart of darkness, so to speak, as Joyce famously pointed out. In tragedy, we are both victim and victimizer. We are equally the cause of suffering, and also the site of suffering. In tragedy, we fleetingly experience dualism reconciled. We are brought into the radical present where everything is possible but also everything is already lost.

One thing that has been occurring to me these past few days is how thoroughly theatrical the Bush regime is. Like the actors at the helm in the 3rd Reich, these guys know how to put on a show. I remember attending a round table discussion at the Taper shortly after the Columbine tragedy. It was the usual dog and pony show, very similar, in fact, to the round table discussion the LA Weekly recently published. Everyone bemoaning the state of the arts, etc. etc. Murray was there, talking about the importance of the tragic view and the Greeks. I recall mentioning my sense that the children who had staged this horrific drama at Columbine where symptoms of a culture that had lost it's connection to vital rituals. Probably everybody has used those two sociopaths as illustrations of something, but I think there is something that could be called cultural health, and that it involves some contact with mortality, with the terror of mortality and existance generally. George W. Bush, it seems to me, is another symptom of our general ill-health as a culture. Hmm, but isn't it the fascists who are always decrying cultural decadence, etc? On that note…back to you…

GZ

ABOUT JOHN STEPPLINGPlaywright, director, screenwriter and teacher, Steppling was an original founding member of the Padua Hills Playwrights Festival and has had his plays produced in London, LA, New York, Paris, San Francisco, and Poland. Plays include The Shaper, Teenage Wedding, Neck, Dog Mouth, The Thrill, Wheel of Fortune and My Crummy Job. A collection of his work was published by Sun and Moon Press in 1999 (Sea of Cortez and Other Plays). He is a Rockefeller Fellow, multiple NEA recipient, and PEN-West winner. His last film credit was Animal Factory (directed by Steve Buscemi 2000). He now lives in Krakow, Poland with his wife Anna Kuros, and teaches at the National Film School in Lodz.ABOUT GUY ZIMMERMANGuy Zimmerman is the Artistic Director of Padua Playwrights. Since 2001, he has staged award-winning productions of new plays by numerous contemporary playwrights (including DogMouth, written and directed by John Steppling) in Los Angeles and New York. He also serves as Supervising Editor of Padua Press, publishing anthologies of new work that are distributed nationally through TCG. Among his teachers are Ken McCleod Katha Pollit and Mark Crispin Miller. His plays include La Clarita, Hide, Vagrant, The Inside Job and The Wasps.** A note on the Frankfurt School —The "Frankfurt school" scholars were all directly, or indirectly associated with the Institute for Social Research, in Frankfurt, Germany. Leading lights of the "school" comprised Theodor W. Adorno (philosopher, sociologist and musicologist), Walter Benjamin (essayist and literary critic), Herbert Marcuse (philosopher), Max Horkheimer (philosopher, sociologist), and later, Jurgen Habermas. Political Psychologist Erich Fromm, was also a member of this group. Each of these thinkers believed, and shared Karl Marx’s theory of Historical Materialism. Each of these individuals observed the beginning of Communism in Russia, and the rise of fascism in Italy. They lived through the first world war, the rise and fall of Hitler, and of course the devastation of the Holocaust and the postwar Cold War. They formed reactions that were attempts to reconcile Marxist theory with the reality of what the people and governments of the world were going through. Each member of the Frankfurt school adjusted Marxism with his additions, or "fix" if you will. They then used the "fixed" Marxist theory as a measure modern society needed to meet. These ideas came to be known as "Critical Theory."

GO BACK TO PART ONE OF THIS EXCHANGE

COMMENTS TO THESE ARTICLES MAY BE POSTED AT THEIR SPECIAL BLOGSPHERE SPOT: http://cyranosjournal.blogspot.com/2005/09/steppling-zimmerman-dialogue-about.html#comments

Be sure to read these simple instructions if you have never posted a blog with Cyrano before. |