|

|

|

|

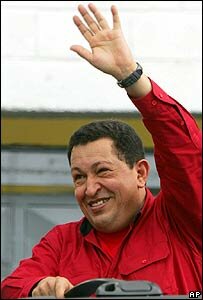

Venezuelan President Chavez: Stuck in the crow of global capitalism. An itch they'd love to scratch...

|

Bolivia is now also in the crosshairs of the empire. Only the unexpected quagmire in Iraq has kept the Americans from intervening more aggressively in this area, their traditional "backyard".

|

Today, the United States is the foremost proponent of recolonization and leading antagonist of revolutionary change throughout the world. Emerging from World War II relatively unscathed and superior to all other industrial countries in wealth, productive capacity, and armed might, the United States became the prime purveyor and guardian of global capitalism. Judging by the size of its financial investments and military force, judging by every imperialist standard except direct colonization, the U.S. empire is the most formidable in history, far greater than Great Britain in the nineteenth century or Rome during antiquity.

A Global Military Empire

The exercise of U.S. power is intended to preserve not only the

international capitalist system but U.S. hegemony of that system.

The Pentagon's "Defense Planning Guidance" draft (1992) urges the

United States to continue to dominate the international system by

"discouraging the advanced industrialized nations from

challenging our leadership or even aspiring to a larger global or

regional role." By maintaining this dominance, the Pentagon

analysts assert, the United States can insure "a market-oriented

zone of peace and prosperity that encompasses more than two-

thirds of the world's economy".

This global power is immensely costly. Today, the United

States spends more on military arms and other forms of "national

security" than the rest of the world combined. U.S. leaders

preside over a global military apparatus of a magnitude never

before seen in human history. In 1993 it included almost a half-

million troops stationed at over 395 major military bases and

hundreds of minor installations in thirty-five foreign countries,

and a fleet larger in total tonnage and firepower than all the

other navies of the world combined, consisting of missile

cruisers, nuclear submarines, nuclear aircraft carriers,

destroyers, and spy ships that sail every ocean and make port on

every continent. U.S. bomber squadrons and long-range missiles

can reach any target, carrying enough explosive force to

destroy entire countries with an overkill capacity of more than

8,000 strategic nuclear weapons and 22,000 tactical ones. U.S.

rapid deployment forces have a firepower in conventional

weaponry vastly superior to any other nation's, with an ability

to slaughter with impunity--as the massacre of Iraq demonstrated

in 1990-91.

Since World War II, the U.S. government has given more than

$200 billion in military aid to train, equip, and subsidize more

than 2.3 million troops and internal security forces in more than

eighty countries, the purpose being not to defend them from

outside invasions but to protect ruling oligarchs and

multinational corporate investors from the dangers of domestic

anti-capitalist insurgency. Among the recipients have been some

of the most notorious military autocracies in history, countries

that have tortured, killed or otherwise maltreated large numbers

of their citizens because of their dissenting political views, as

in Turkey, Zaire, Chad, Pakistan, Morocco, Indonesia, Honduras,

Peru, Colombia, El Salvador, Haiti, Cuba (under Batista),

Nicaragua (under Somoza), Iran (under the Shah), the Philippines

(under Marcos), and Portugal (under Salazar).

U.S. leaders profess a dedication to democracy. Yet over the

past five decades, democratically elected reformist governments

in Guatemala, Guyana, the Dominican Republic, Brazil, Chile,

Uruguay, Syria, Indonesia (under Sukarno), Greece, Argentina,

Bolivia, Haiti, and numerous other nations were overthrown by

pro-capitalist militaries that were funded and aided by the U.S.

national security state.

The U.S. national security state has participated in covert

actions or proxy mercenary wars against revolutionary governments

in Cuba, Angola, Mozambique, Ethiopia, Portugal, Nicaragua,

Cambodia, East Timor, Western Sahara, and elsewhere, usually with

dreadful devastation and loss of life for the indigenous

populations. Hostile actions have been directed against reformist

governments in Egypt, Lebanon, Peru, Iran, Syria, Zaire, Jamaica,

South Yemen, the Fiji Islands, and elsewhere.

Since World War II, U.S. forces have directly invaded or

launched aerial attacks against Vietnam, the Dominican Republic,

North Korea, Laos, Cambodia, Lebanon, Grenada, Panama, Libya,

Iraq, and Somalia, sowing varying degrees of death and

destruction.

Before World War II, U.S. military forces waged a bloody and

protracted war of conquest in the Philippines in 1899-1903. Along

with fourteen other capitalist nations, the United States invaded

socialist Russia in 1918-21. U.S. expeditionary forces fought in

China along with other Western armies to suppress the Boxer

Rebellion and keep the Chinese under the heel of European and

North American colonizers. U.S. Marines invaded and occupied

Nicaragua in 1912 and again in 1926 to 1933; Cuba, 1898 to 1902;

Mexico, 1914 and 1916; Honduras, six invasions between 1911 to

1925; Panama, 1903-1914, and Haiti, 1915 to 1934.

Why Intervention?

Why has a professedly peace-loving, democratic nation found it

necessary to use so much violence and repression against so many

peoples in so many places? An important goal of U.S. policy is to

make the world safe for the Fortune 500 and its global system of

capital accumulation. Governments that strive for any kind of

economic independence or any sort of populist redistributive

politics, who have sought to take some of their economic surplus

and apply it to not-for-profit services that benefit the

people--such governments are the ones most likely to feel the

wrath of U.S. intervention or invasion.

The designated "enemy" can be a reformist, populist,

military government as in Panama under Torrijo (and even under

Noriega), Egypt under Nasser, Peru under Velasco, and Portugal

under the MFA; a Christian socialist government as in Nicaragua

under the Sandinistas; a social democracy as in Chile under

Allende, Jamaica under Manley, Greece under Papandreou, and the

Dominican Republic under Bosch; a Marxist-Leninist government as

in Cuba, Vietnam, and North Korea; an Islamic revolutionary order

as in Libya under Qaddafi; or even a conservative militarist

regime as in Iraq under Saddam Hussein--if it should get out of

line on oil prices and oil quotas.

The public record shows that the United States is the

foremost interventionist power in the world. There are varied and

overlapping reasons for this:

Protect Direct Investments. In 1907, Woodrow Wilson

recognized the support role played by the capitalist state on

behalf of private capital:

Since trade ignores national boundaries and the manufacturer

insists on having the world as a market, the flag of his nation

must follow him, and the doors of the nations which are closed

against him must be battered down. Concessions obtained by

financiers must be safeguarded by ministers of state, even if the

sovereignty of unwilling nations be outraged in the process.

Colonies must be obtained or planted, in order that no useful

corner of the world may be overlooked or left unused.

Later, as president of the United States, Wilson noted that

the United States was involved in a struggle to "command the

economic fortunes of the world."

During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries,

large U.S. investments in Central America and the Caribbean

brought frequent military intercession, protracted war, prolonged

occupation, or even direct territorial acquisition, as with

Hawaii, Puerto Rico, and the Panama Canal Zone. The investments

were often in the natural resources of the country: sugar,

tobacco, cotton, and precious metals. In large part, the

interventions in the Gulf in 1991 (see chapter six) and in

Somalia in 1993 (chapter seven) were respectively to protect oil

profits and oil prospects.

In the post cold-war era, Admiral Charles Larson noted that,

although U.S. military forces have been reduced in some parts of

the world, they remain at impressive levels in the Asia-Pacific

area because U.S. trade in that region is greater than with

either Europe or Latin America. Naval expert Charles Meconis also

pointed to "the economic importance of the region" as the reason

for a major U.S. military presence in the Pacific (see Daniel

Schirmer, Monthly Review, July/August 1994). In these instances,

the sword follows the dollar.

Create Opportunities for New Investments. Sometimes the

dollar follows the sword, as when military power creates

opportunities for new investments. Thus, in 1915, U.S. leaders,

citing "political instability," invaded Haiti and crushed the

popular militia. The troops stayed for nineteen years. During

that period French, German, and British investors were pushed out

and U.S. firms tripled their investments in Haiti.

More recently, Taiwanese companies gave preference to U.S.

firms over Japanese ones because the U.S. military was protecting

Taiwan. In 1993, Saudi Arabia signed a $6 billion contract for

jet airliners exclusively with U.S. firms. Having been frozen out

of the deal, a European consortium charged that Washington had

pressured the Saudis, who had become reliant on Washington for

their military security in the post-Gulf War era.

Preserving Politico-Economic Domination and the

International Capital Accumulation System. Specific investments

are not the only imperialist concern. There is the overall

commitment to safeguarding the global class system, keeping the

world's land, labor, natural resources, and markets accessible to

transnational investors. More important than particular holdings

is the whole process of investment and profit. To defend that

process the imperialist state thwarts and crushes those popular

movements that attempt any kind of redistributive politics,

sending a message to them and others that if they try to better

themselves by infringing upon the prerogatives of corporate

capital, they will pay a severe price.

In two of the most notable U.S. military interventions,

Soviet Russia in 1918-20 and Vietnam in 1954-73, most of the

investments were European, not American. In these and other such

instances, the intent was to prevent the emergence of competing

social orders and obliterate all workable alternatives to the

capitalist client-state. That remains the goal to this day. The

countries most recently targeted being South Yemen, North Korea,

and Cuba.

Ronald Reagan was right when he avowed that his invasion of

Grenada was not to protect the U.S. nutmeg supply. There was

plenty of nutmeg to be got from Africa. He was acknowledging that

Grenada's natural resources were not crucial. Nor would the

revolutionary collectivization of a poor nation of 102,000 souls

represent much of a threat or investment loss to global

capitalism. But if enough countries follow that course, it

eventually would put the global capitalist system at risk.

Reagan's invasion of Grenada served notice to all other

Caribbean countries that this was the fate that awaited any

nation that sought to get out from under its client-state status.

So the invaders put an end to the New Jewel Movement's

revolutionary programs for land reform, health care, education,

and cooperatives. Today, with its unemployment at new heights and

its poverty at new depths, Grenada is once again firmly bound to

the free market world. Everyone else in the region indeed has

taken note.

The imperialist state's first concern is not to protect the

direct investments of any particular company, although it

sometimes does that, but to protect the global system of private

accumulation from competing systems. The case of Cuba illustrates

this point. It has been pointed out that Washington's embargo

against Cuba is shutting out U.S. business from billions of

dollars of attractive investment and trade opportunities. From

this it is mistakenly concluded that U.S. policy is not propelled

by economic interests. In fact, it demonstrates just the

opposite, an unwillingness to tolerate those states that try to

get out from under the global capitalist system.

The purpose of the capitalist state is to do things for the

advancement of the entire capitalist system that individual

corporate interests cannot do. Left to their own competitive

devices, business firms are not willing to abide by certain rules

nor tend to common systemic interests. This is true both for the

domestic economy and foreign affairs. Like any good capitalist

organization, a business firm may have a general long-range

interest in seeing Cuban socialism crushed, but it might have a

more tempting immediate interest in doing a profitable business

with the class enemy. It remains for the capitalist state to

force individual companies back in line.

What is at stake is not the investments within a particular

Third World country but the long-range security of the entire

system of transnational capitalism. No country that pursues an

independent course of development shall be allowed to prevail as

a dangerous example to other nations.

Common Confusions

Some critics have argued that economic factors have not exerted

an important influence on U.S. interventionist policy because

most interventions are in countries that have no great natural

treasures and no large U.S. investments, such as, Grenada, El

Salvador, Nicaragua, and Vietnam. This is like saying that police

are not especially concerned about protecting wealth and property

because most of their actions take place in poor neighborhoods.

Interventionist forces do not go where capital exists as such;

they go where capital is threatened. They have not intervened in

affluent Switzerland, for instance, because capitalism in that

country is relatively secure and unchallenged. But if leftist

parties gained power in Bern and attempted to nationalize Swiss

banks and major properties, it very likely would invite the

strenuous attentions of the Western industrial powers.

Some observers maintain that intervention is bred by the

national-security apparatus itself, the State Department, the

National Security Council, and the CIA. These agencies conjure up

new enemies and crises because they need to justify their own

existence and augment their budget allocations. This view avoids

the realities of class interest and power. It suggests that

policymakers serve no purpose other than policymaking for their

own bureaucratic aggrandizement. Such a notion reverses cause and

effect. It is a little like saying the horse is the cause of the

horse race. It treats the national security state as the

originator of intervention when in fact it is but one of the

major instruments. U.S. leaders were engaging in interventionist

actions long before the CIA and NSC existed.

One of those who argues that the state is a self-generated

aggrandizer is Richard Barnet, who dismisses the "more familiar

and more sinister motives" of economic imperialism. Whatever

their economic systems, all large industrial states, he

maintains, seek to project power and influence in a search for

security and domination. To be sure, the search for security is a

real consideration for every state, especially in a world in

which capitalist power is hegemonic and ever threatening. But the

capital investments of multinational corporations expand in a far

more dynamic way than the economic expansion manifested by

socialist or precapitalist governments.

In fact, the case studies in Barnet's book Intervention and

Revolution point to business, rather than the national security

bureaucracies, as the primary motive of U.S. intervention. Anti-

communism and the Soviet threat seem less a source for policy

than a propaganda ploy to frighten the American public and rally

support for overseas commitments. The very motives Barnet

dismisses seem to be operative in his case studies of Greece,

Iran, Lebanon, and the Dominican Republic, specifically the

desire to secure access to markets and raw materials and the

need, explicitly stated by various policymakers, to protect free

enterprise throughout the world.

Some might complain that the foregoing analysis is

"simplistic" because it ascribes all international events to

purely economic and class motives and ignores other variables

like geopolitics, culture, ethnicity, nationalism, ideology, and

morality. But I do not argue that the struggle to maintain

capitalist global hegemony explains everything about world

politics nor even everything about U.S. foreign policy. However,

it explains quite a lot; so is it not time we become aware of it?

If mainstream opinion makers really want to portray

political life in all its manifold complexities, then why are

they so studiously reticent about the immense realities of

imperialism?

The existence of other variables such as nationalism,

militarism, the search for national security, and the pursuit of

power and hegemonic dominance, neither compels us to dismiss

economic realities, nor to treat these other variables as

insulated from class interests. Thus, the desire to extend U.S.

strategic power into a particular region is impelled at least in

part by a desire to stabilize the area along lines that are

favorable to politico-economic elite interests--which is why the

region becomes a focus of concern in the first place.

In other words, various considerations work with circular

effect upon each other. The growth in overseas investments invite

a need for military protection. This, in turn, creates a need to

secure bases and establish alliances with other nations. The

alliances now expand the "defense" perimeter that must be

maintained. So a particular country becomes not only an

"essential" asset for our defense but must itself be defended,

like any other asset.

Inventing Enemies

As noted in the previous chapter, the U.S. empire is

neoimperialist in its operational mode. With the exception of a

few territorial possessions, U.S. overseas expansion has relied

on indirect control rather than direct possession. This is not to

say that U.S. leaders are strangers to annexation and conquest.

Most of what is now the continental United States was forcibly

wrested from Native American nations. California and all of the

Southwest USA were taken from Mexico by war. Florida and Puerto

Rico were seized from Spain.

U.S. leaders must convince the American people that the

immense costs of empire are necessary for their security and

survival. For years we were told that the great danger we faced

was "the World Communist Menace with its headquarters in Moscow."

U.S. citizens accepted a crushing tax burden to pay for

"defense," to win the superpower arms race and "contain Soviet

aggression wherever it might arise." Since the demise of the

USSR, our political leaders have been warning us that the world

is full of other dangerous adversaries, who apparently had been

previously overlooked.

Who are these evil adversaries who wait to spring upon the

USA the moment we drop our guard or the moment we make real cuts

in our gargantuan military budget? Why do they stalk us instead

of, say, Denmark or Brazil? This scenario of a world of enemies

was used by the rulers of the Roman empire and by nineteenth-

century British imperialists. Enemies always had to be

confronted, requiring more interventions and more expansion. And

if enemies were not to be found, they would be invented.

Americans have little cause to take pride in being part of

"our" mighty empire, for what that empire does to peoples abroad

is nothing to be proud of. And at home, the policies of empire

benefit the dominant interests rather than the interests of the

common citizenry. When Washington says "our" interests must be

protected abroad, we might question whether all of us are

represented by the goals pursued. Far-off countries, previously

unknown to most Americans, suddenly become vital to "our"

interests. To protect "our" oil in the Middle East and "our"

resources and "our" markets elsewhere, our sons and daughters

have to participate in overseas military ventures, and our taxes

are needed to finance these ventures.

The next time "our" oil in the Middle East is in jeopardy,

we might remember that relatively few of us own oil stock. Yet

even portfolio-deprived Americans are presumed to have a common

interest with Exxon and Mobil because they live in an economy

dependent on oil. It is assumed that if the people of other lands

wrested control of their oil away from the big U.S. companies,

they would refuse to sell it to us. Supposedly they would prefer

to drive us into the arms of competing producers and themselves

into ruination, denying themselves the billions of dollars they

might earn on the North American market.

In fact, nations that acquire control of their own resources

do not act so strangely. Cuba, Vietnam, North Korea, Libya, and

others would be happy to have access to markets in this country,

selling at prices equal to or more reasonable than those offered

by the giant multinationals. So when Third World peoples, through

nationalization, revolution, or both, take over the oil in their

own land, or the copper, tin, sugar, or other industries, it does

not hurt the interests of the U.S. working populace. But it

certainly hurts the multinational conglomerates that once

profited so handsomely from these enterprises.

Who Pays? Who Profits?

We are made to believe that the people of the United States have

a common interest with the giant multinationals, the very

companies that desert our communities in pursuit of cheaper labor

abroad. In truth, on almost every issue the people are not in the

same boat with the big companies. Policy costs are not equally

shared; benefits are not equally enjoyed. The "national" policies

of an imperialist country reflect the interests of that country's

dominant socio-economic class. Class rather than nation-state

more often is the crucial unit of analysis in the study of

imperialism.

[The liberals' blind spot]

The tendency to deny the existence of conflicting class

interests when dealing with imperialism leads to some serious

misunderstandings. For example, liberal writers like Kenneth

Boulding and Richard Barnet have pointed out that empires cost

more than they bring in, especially when wars are fought to

maintain them. Thus, from 1950 to 1970, the U.S. government spent

several billions of dollars to shore up a corrupt dictatorship in

the Philippines, hoping to protect about $1 billion in U.S.

investments in that country. At first glance it does not make

sense to spend $3 billion to protect $1 billion. Saul Landau has

made this same point in regard to the costs of U.S. interventions

in Central America: they exceed actual U.S. investments. Barnet

notes that "the costs of maintaining imperial privilege always

exceed the gains." From this it has been concluded that empires

simply are not worth all the expense and trouble. Long before

Barnet, the Round Table imperialist policymakers in Great Britain

wanted us to believe that the empire was not maintained because

of profit; indeed "from a purely material point of view the

Empire is a burden rather than a source of gain" (Round Table,

vol 1, 232-39, 411).

To be sure, empires do not come cheap. Burdensome

expenditures are needed for military repression and prolonged

occupation, for colonial administration, for bribes and arms to

native collaborators, and for the development of a commercial

infrastructure to facilitate extractive industries and capital

penetration. But empires are not losing propositions for

everyone. The governments of imperial nations may spend more than

they take in, but the people who reap the benefits are not the

same ones who foot the bill. As Thorstein Veblen pointed out in

The Theory of the Business Enterprise (1904), the gains of empire

flow into the hands of the privileged business class while the

costs are extracted from "the industry of the rest of the

people." The transnationals monopolize the private returns of

empire while carrying little, if any, of the public cost. The

expenditures needed in the way of armaments and aid to make the

world safe for General Motors, General Dynamics, General

Electric, and all the other generals are paid by the U.S.

government, that is, by the taxpayers.

So it was with the British empire in India, the costs of

which, Marx noted a half-century before Veblen, were "paid out of

the pockets of the people of England," and far exceeded what came

back into the British treasury. He concluded that the advantage

to Great Britain from her Indian Empire was limited to the "very

considerable" profits which accrued to select individuals, mostly

a coterie of stockholders and officers in the East India Company

and the Bank of England.

Likewise, beginning in the late nineteenth century and

carrying over into the twentieth, the German conquest of

Southwest Africa "remained a loss-making enterprise for the

German taxpayer," according to historian Horst Drechsler, yet "a

number of monopolists still managed to squeeze huge profits out

of the colony in the closing years of German colonial

domination." And imperialism is in the service of the few

monopolists not the many taxpayers.

In sum, there is nothing irrational about spending three

dollars of public money to protect one dollar of private

investment--at least not from the perspective of the investors.

To protect one dollar of their money they will spend three, four,

and five dollars of our money. In fact, when it comes to

protecting their money, our money is no object.

Furthermore, the cost of a particular U.S. intervention must

be measured not against the value of U.S. investments in the

country involved but against the value of the world investment

system. It has been noted that the cost of apprehending a bank

robber may occasionally exceed the sum that is stolen. But if

robbers were allowed to go their way, this would encourage others

to follow suit and would put the entire banking system in

jeopardy.

At stake in these various wars of suppression, as already

noted, is not just the investments in any one country but the

security of the whole international system of finance capital. No

country is allowed to pursue an independent course of self-

development. None is permitted to go unpunished and undeterred.

None should serve as an inspiration or source of material support

to other nations that might want to pursue a politico-economic

path other than the maldevelopment offered by global capitalism.

The Myth of Popular Imperialism

Those who think of empire solely as an expression of national

interests rather than class interests are bound to misinterpret

the nature of imperialism. In his American Diplomacy 1900-1950,

George Kennan describes U.S. imperialist expansion at the end of

the nineteenth century as a product of popular aspiration: the

American people "simply liked the smell of empire"; they wanted

"to bask in the sunshine of recognition as one of the great

imperial powers of the world."

In The Progressive (October 1984), the liberal writers John

Buell and Matthew Rothschild comment that "the American psyche is

pegged to being biggest, best, richest, and strongest. Just

listen to the rhetoric of our politicians." But does the

politician's rhetoric really reflect the sentiments of most

Americans, who in fact come up as decidedly noninterventionist in

most opinion polls? Buell and Rothschild assert that "when a

Third World nation--whether it be Cuba, Vietnam, Iran, or

Nicaragua--spurns our way of doing things, our egos ache. . ."

Actually, such countries spurn the ways of global corporate

capitalism--and this is what U.S. politico-economic leaders will

not tolerate. Psychologizing about aching collective egos allows

us to blame imperialism on ordinary U.S. citizens who are neither

the creators nor beneficiaries of empire.

In like fashion, the historian William Appleman Williams, in

his Empire As a Way of Life, scolds the American people for

having become addicted to the conditions of empire. It seems "we"

like empire. "We" live beyond our means and need empire as part

of our way of life. "We" exploit the rest of the world and don't

know how to get back to a simpler life. The implication is that

"we" are profiting from the runaway firms that are exporting our

jobs and exploiting Third World peoples. "We" decided to send

troops into Central America, Vietnam, and the Middle East and

thought to overthrow democratic governments in a dozen or more

countries around the world. And "we" urged the building of a

global network of counterinsurgency, police torturers, and death

squads in numerous countries.

For Williams, imperialist policy is a product of mass

thinking. In truth, ordinary Americans usually have opposed

intervention or given only lukewarm support. Opinion polls during

the Vietnam War showed that the public wanted a negotiated

settlement and withdrawal of U.S. troops. They supported the idea

of a coalition government in Vietnam that included the

communists, and they supported elections even if the communists

won them.

Pollster Louis Harris reported that, during 1982-84

Americans rejected increased military aid for El Salvador and its

autocratic military machine by more than 3 to 1. Network surveys

found that 80 percent opposed sending troops to that country; 67

percent were against the U.S. mining of Nicaragua's harbors; and

2 to 1 majorities opposed aid to the Nicaraguan contras (the

rightwing CIA-supported mercenary army that was waging a brutal

war of attrition against Nicaraguan civilians). A 1983 Washington

Post/ABC News poll found that, by a 6 to 1 ratio, our citizens

opposed any attempt by the United States to overthrow the

Nicaraguan government. By more than 2 to 1 the public said the

greatest cause of unrest in Central America was not subversion

from Cuba, Nicaragua, or the Soviet Union but "poverty and the

lack of human rights in the area."

Even the public's superpatriotic yellow-ribbon binge during

the more recent Gulf War of 1991 was not the cause of the war

itself. It was only one of the disgusting and disheartening by-

products. Up to the eve of that conflict, opinion polls showed

Americans favoring a negotiated withdrawal of Iraqi troops rather

than direct U.S. military engagement. But once U.S. forces were

committed to action, then the "support-our-troops" and "go for

victory" mentality took hold of the public, pumped up as always

by a jingoistic media propaganda machine.

Once war comes, especially with the promise of a quick and

easy victory, some individuals suspend all critical judgment and

respond on cue like mindless superpatriots. One can point to the

small businessman in Massachusetts, who announced that he was a

"strong supporter" of the U.S. military involvement in the Gulf,

yet admitted he was not sure what the war was about. "That's

something I would like know," he stated. "What are we fighting

about?" (New York Times, November 15, 1990)

In the afterglow of the Gulf triumph, George Bush had a 93

percent approval rating and was deemed unbeatable for reelection

in 1992. Yet within a year, Americans had come down from their

yellow ribbon binge and experienced a postbellum depression,

filled with worries about jobs, money, taxes and other such

realities. Bush's popularity all but evaporated and he was

defeated by a scandal-plagued, relatively unknown governor from

Arkansas.

Whether they support or oppose a particular intervention,

the American people cannot be considered the motivating force of

the war policy. They do not sweep their leaders into war on a

tide of popular hysteria. It is the other way around. Their

leaders take them for a ride and bring out the worst in them.

Even then, there are hundreds of thousands who remain actively

opposed and millions who correctly suspect that such ventures are

not in their interest.

Cultural Imperialism

Imperialism exercises control over the communication universe.

American movies, television shows, music, fashions, and consumer

products inundate Latin America, Asia, and Africa, as well as

Western and Eastern Europe. U.S. rock stars and other performers

play before wildly enthusiastic audiences from Madrid to Moscow,

from Rio to Bangkok. U.S. advertising agencies dominate the

publicity and advertising industries of the world.

Millions of news reports, photographs, commentaries,

editorials, syndicated columns, feature stories from U.S. media,

saturate most other countries each year. The average Third World

nation is usually more exposed to U.S. media viewpoints than to

those of neighboring countries or its own backlands. Millions of

comic books and magazines, condemning communism and boosting the

wonders of the free market, are translated into dozens of

languages and distributed by U.S. (dis)information agencies. The

CIA alone owns outright over 200 newspapers, magazines, wire

services and publishing houses in countries throughout the world.

U.S. government-funded agencies like the National Endowment

for Democracy and the Agency for International Development, along

with the Ford Foundation and other such organizations, help

maintain Third World universities, providing money for academic

programs, social science institutes, research, student

scholarships, and textbooks supportive of a free market

ideological perspective. Right-wing Christian missionary agencies

preach political quiescence and anticommunism to native

populations. The AFL-CIO's American Institute for Free Labor

Development (AIFLD), with ample State Department funding, has

actively infiltrated Third World labor organizations or built

compliant unions that are more anticommunist than pro-worker.

AIFLD graduates have been linked to coups and counterinsurgency

work in various countries. Similar AFL-CIO undertakings operate

in Africa and Asia.

The CIA has infiltrated important political organizations in

numerous countries and maintains agents at the highest levels of

various governments, including heads of state, military leaders,

and opposition political parties. Washington has financed

conservative political parties in Latin America, Asia, Africa,

and Western and Eastern Europe. Their major qualification is that

they be friendly to Western capital penetration. While federal

law prohibits foreigners from making campaign contributions to

U.S. candidates, Washington policymakers reserve the right to

interfere in the elections of other countries, such as Italy, the

Dominican Republic, Panama, Nicaragua, and El Salvador, to name

only a few. U.S. leaders feel free to intrude massively upon the

economic, military, political, and cultural practices and

institutions of any country they so choose. That's what it means

to have an empire.

|